Diagnosis of PCOS in Adolescent Risks Delay

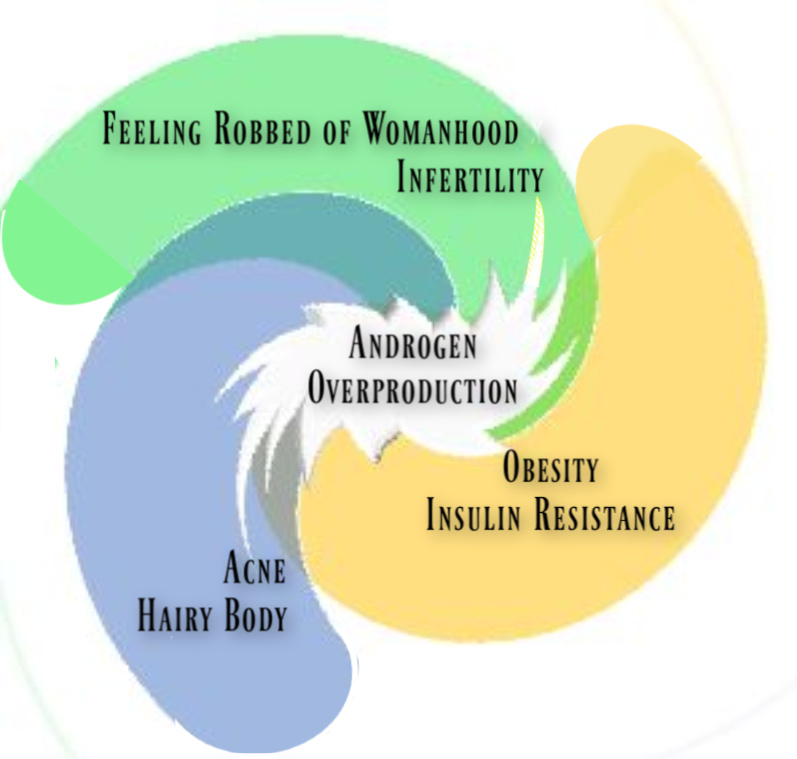

PCOS, polycystic ovarian syndrome, is commonly linked to obesity. It is a complex outcome of disturbed hereditary, hormonal, and environmental influences. The early signs of the disease often manifest in children under 8 years of age, much before puberty sets its foot in.

The medical literature, however, lists it under sex hormones disorder in women of reproductive age. It thus negates the very existence of PCOS in children. Most shy away from as much as considering it a possibility in adolescent girls, also in them who present with acne and abnormal growth of hair on their face and body, especially if they fall in the range of normal for BMI.

Incidence

Polycystic ovary syndrome is the most common hormone disorder in young girls. The incidence varies. On average, 1 in 10 women in the childbearing age group is affected, whereas it is only 1 in 100 among teenagers. This difference in the incidence is due to the common misconception that PCOS develops only in the overweight adolescents. The obese girls are more likely than normal-weight girls to receive a diagnosis by their doctor. In adolescents who are neither obese nor trying to conceive, the diagnosis often gets missed. Most of those who do get diagnosed under 19 years of age, fall high up on the BMI scale, and are already feeling robbed of their womanhood.

Under-diagnosis of PCOS in adolescent girls creates an impression that PCOS is rare before the age of 20. Moreover, the fact that the risk of the disease could have set in early during childhood is generally not known. The few who are aware tend to deny the possibility even when they come across a preteens-child with signs of excessive androgens.

Children in their middle childhood development phase are quite confused about the changes that their body is going through. And the parents, they are neither aware of the risk factors of polycystic ovaries, nor can they perceive that those innocent looking symptoms of PCOS that surface at a tender age 7 years would define their little daughter's quality of life across her life course.

Identify children at risk of PCOS

Genetic predisposition to polycystic ovarian syndrome

PCOS runs in families. Yet, per se, it can not be defined as a genetic disorder. A typical genetic disorder has a well defined clinical picture, which polycystic ovarian syndrome does not have. The signs and symptoms of the syndrome vary from person to person. The exact pattern of its inheritance is not known. It is a polygenic disorder. The genetic factors include genetic variations of several genes, which account for about 70% of the variance in the clinical course of the disease.

Over 200 gene variations have been recorded in these cases

The gene variation alters the expression of the gene that leads to ovarian dysfunction. Essentially, the genes involved in the functioning of the sex hormones receptors and Leptin receptors are affected. The defect in these genes disrupts the series of chemical reactions occurring within the cells and impairs the functions of the ovaries.

Lifestyle & environmental factors lead to epigenetic changes

The genetic variations alone cannot bring about full-blown PCOS. The fully expressed clinical picture is an outcome of lifestyle and environmental influences that work in tandem with the defective genes.

The awareness of genetic predisposition is, however, crucial to identify children at risk, much before the adolescent girls are physically and emotionally marred.

Fetal programming of PCOS

Besides genes, the mother’s environment and lifestyle influence the fetal programming of PCOS. Excessive androgens modulate fetal endocrine system development. As a result, the female baby is prone to develop signs of the syndrome as she grows.

However, the effect of maternal milieu on her offspring is not limited to fetal life. It continues after birth, through infancy well into tender years of early childhood development. It brings about epigenetic modifications. Epigenetic changes are heritable changes in gene expression, which play a crucial role in the origin and progress of the disease right up to adulthood of the female child.

Symptoms of PCOS in early childhood

The clinical sign of PCOS in early childhood usually merge with pubertal changes. One of it is premature adrenarche - development of pubic hair at 6-7 years of age in a girl born with above-average or low birth weight expected for her gestational age.

The other signs are emotional instability and excessive weight gain from about 5 years of age in a child who is generally not inclined to play active sports. Obesity at 14 years of age is associated with a 61% higher risk of manifesting symptoms of PCOS at 31 years of age.

Weight gain in children is natural and desirable. It is considered abnormal when the discrepancy between weight gain and height gain continues to increase on the percentile chart for child growth. Moreover, weight gain is accompanied by a significant increase in the waist size of the child.

Some may progress to develop dark skin patches. These dark ill-defined velvety patches appear in body folds, such as behind the neck, in the armpits, or groin. They, therefore, remain hidden and often go unattended for a long time. The syndrome, however, continues to progress, and the metabolic disorder evolves. Early alterations in the metabolic status increases the risk of the full-fledged expression of polycystic ovarian syndrome during adulthood.

Identifying children at risk for PCOS offers an opportunity to introduce healthy lifestyle changes much before the disease takes its toll on the beauty and health of young women. The therapy they get is often limited to the treatment of infertility or hirsutism and acne. But the damages incurred by the disorder are much more.

Obesity and PCOS aggravate each other. Early diagnosis is, therefore, essential. It can not only help halt the disease process but also reverse its ill effects. Simple weight management is the answer to this complex problem.

Related pages of interest

Living with PCOS - a true story

Liked what you read just now? Pay it forward!

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.